Trendaavat aiheet

#

Bonk Eco continues to show strength amid $USELESS rally

#

Pump.fun to raise $1B token sale, traders speculating on airdrop

#

Boop.Fun leading the way with a new launchpad on Solana.

Arvind Narayanan

Princeton CS prof. Director @PrincetonCITP. I use X to share my research and commentary on the societal impact of AI.

BOOK: AI Snake Oil. Views mine.

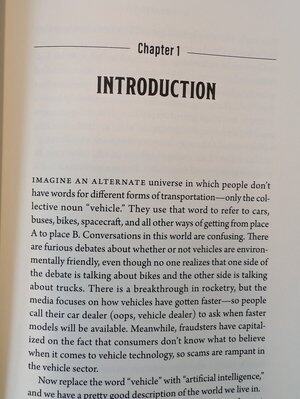

Many people have told us that this is one of the most memorable opening paragraphs they've come across in a book. 🙏 The funny thing is that the analogy wasn't a hit with reviewers, so we were going to take it out, but had a last minute change of heart because our editor liked it. I've learned that it's very hard to predict which parts will resonate with readers, whether in a book, online essay, or any other format. Publishing is always a nerve-wracking shot in the dark.

27,6K

My experience with ChatGPT Agent so far: I've failed to find any use cases that _cannot_ be handled by Deep Research and yet can be successfully completed by Agent without running into any stumbling blocks like janky web forms or access restrictions.

I'm sure I'll find some uses, but it will end up being a small fraction of tasks that come up in my workflows.

If this is the case, it won't make sense to try to do new tasks using Agent unless it's a task that I would otherwise spend hours on (or would need to repeat on a daily basis). If my expectation is that Agent will succeed with a 5% probability, and it takes 10-20 minutes of trying painfully hard before giving up, it's not worth my time to even find out if Agent can do it. I would only use it if I somehow already knew that it's a task that Agent can handle.

Given all this, I continue to think that task-specific agents will be more successful for the foreseeable future.

8,99K

Back in grad school, when I realized how the “marketplace of ideas” actually works, it felt like I’d found the cheat codes to a research career. Today, this is the most important stuff I teach students, more than anything related to the substance of our research.

A quick preface: when I talk about research success I don’t mean publishing lots of papers. Most published papers gather dust because there is too much research in any field for people to pay attention to. And especially given the ease of putting out pre-prints, research doesn’t need to be officially published in order to be successful. So while publications may be a prerequisite for career advancement, they shouldn’t be the goal. To me, research success is authorship of ideas that influence your peers and make the world a better place.

So the basic insight is that there are too many ideas entering the marketplace of ideas, and we need to understand which ones end up being influential. The good news is that quality matters — other things being equal, better research will be more successful. The bad news is that quality is only weakly correlated with success, and there are many other factors that matter.

First, give yourself multiple shots on goal. The role of luck is a regular theme of my career advice. It’s true that luck matters a lot in determining which papers are successful, but that doesn’t mean resigning yourself to it. You can increase your “luck surface area”.

For example, if you always put out preprints, you get multiple chances for your work to be noticed: once with the preprint and once with the publication (plus if you’re in a field with big publication lags, you can make sure the research isn’t scooped or irrelevant by the time it comes out).

More generally, treat research projects like startups — accept that there is a very high variance in outcomes, with some projects being 10x or 100x more successful than others. This means trying lots of different things, taking big swings, being willing to pursue what your peers consider to be bad ideas, but with some idea of why you might potentially succeed where others before you failed. Do you know something that others don’t, or do they know something that you don’t? And if you find out it’s the latter, you need to be willing to quit the project quickly, without falling prey to the sunk cost fallacy.

To be clear, success is not all down to luck — quality and depth matter a lot. And it takes a few years of research to go deep into a topic. But spending a few years researching a topic before you publish anything is extremely risky, especially early in your career. The solution is simple: pursue projects, not problems.

Projects are long-term research agendas that last 3-5 years or more. A productive project could easily produce a dozen or more papers (depending on the field). Why pick projects instead of problems? If your method is to jump from problem to problem, the resulting papers are likely to be somewhat superficial and may not have much impact. And secondly, if you’re already known for papers on a particular topic, people are more likely to pay attention to your future papers on that topic. (Yes, author reputation matters a lot. Any egalitarian notion of how people pick what to read is a myth.)

To recap, I usually work on 2-3 long-term projects at a time, and within each project there are many problems being investigated and many papers being produced at various stages of the pipeline.

The hardest part is knowing when to end a project. At the moment you’re considering a new project, you’re comparing something that will take a few years to really come to fruition with a topic where you’re already highly productive. But you have to end something to make room for something new. Quitting at the right time always feels like quitting too early. If you go with your gut, you will stay in the same research area for far too long.

Finally, build your own distribution. In the past, the official publication of a paper served two purposes: to give it the credibility that comes from peer review, and to distribute the paper to your peers. Now those two functions have gotten completely severed. Publication still brings credibility, but distribution is almost entirely up to you!

This is why social media matters so much. Unfortunately social media introduces unhealthy incentives to exaggerate your findings, so I find blogs/newsletters and long-form videos to be much better channels. We are in a second golden age of blogging and there is an extreme dearth of people who can explain cutting-edge research from their disciplines in an accessible way but without dumbing it down like in press releases or news articles. It’s never too early — I started a blog during my PhD and it played a big role in spreading my doctoral research, both within my research community and outside it.

Summary

* Research success doesn’t just mean publication

* The marketplace of ideas is saturated

* Give yourself multiple shots on goal

* Pick projects, not problems

* Treat projects like startups

* Build your own distribution

46,71K

Johtavat

Rankkaus

Suosikit

Ketjussa trendaava

Trendaa X:ssä

Viimeisimmät suosituimmat rahoitukset

Merkittävin